spread the word... in 2012 worldwide release!!

Thursday, December 8, 2011

Tuesday, December 6, 2011

photos

been working on the trailer for months... soon, very soon... in the meantime, some recently unearthed photos from the shoot:

Wednesday, October 26, 2011

fusil, metralla, el pueblo no se calla

"Rifle, machine gun, the people don't run"

(literally: "Rifle, machine gun, the people won't be silenced")

For a long time I thought of this popular Latin American marching slogan as a call to arms... now I think it could just as easily be addressing the the rifle and the machine gun, exclaiming that the people will not be silenced by the thundering violence aimed at them.

The below image has long fascinated me, ever since I saw it in La Paz, on a fake DVD of "Fusil, metralla el pueblo no se calla", the best documentary on the Gas Wars I've yet seen (check it out online). The original video came out a couple of months after the Gas Wars calmed down and Goni fled. This is surely a pirate copy. The layout and words are themselves an excellent record of popular sentiment. The miner with coca in his cheek raising fist at a devilishly white Goni... the gruesome b-film typography evoking the massacre... the stencil-like subtitle at the bottom "The failure of the k'aras (the aymara word for whites)"... the excerpt from a local publication describing current events during the gas wars instead of a description of the contents of the film...

(literally: "Rifle, machine gun, the people won't be silenced")

For a long time I thought of this popular Latin American marching slogan as a call to arms... now I think it could just as easily be addressing the the rifle and the machine gun, exclaiming that the people will not be silenced by the thundering violence aimed at them.

The below image has long fascinated me, ever since I saw it in La Paz, on a fake DVD of "Fusil, metralla el pueblo no se calla", the best documentary on the Gas Wars I've yet seen (check it out online). The original video came out a couple of months after the Gas Wars calmed down and Goni fled. This is surely a pirate copy. The layout and words are themselves an excellent record of popular sentiment. The miner with coca in his cheek raising fist at a devilishly white Goni... the gruesome b-film typography evoking the massacre... the stencil-like subtitle at the bottom "The failure of the k'aras (the aymara word for whites)"... the excerpt from a local publication describing current events during the gas wars instead of a description of the contents of the film...

Friday, September 9, 2011

Movements: spectacular and revolutionary... small and slow

As the post-production of this film enters its second year, we in the creative team grapple with patience. With funds, we would finish within a couple of months... As it is, as we inch forward steadily, we are forced to aim our art beyond the urgency of the topical, beyond the current political battles. This forced transcendence, I think, can be good for art, despite its difficulty. So many artworks leave you thinking, "dang, wish the author would've spent a little more time thinking this all the way through".

I am struck by how much attention is paid to revolutionary fervor, and how little to the long, complex aftermath.

The spectacular moments of 2000 and 2003, when Bolivia was a battleground, have given way to the past 7 years of working out how to construct a new model, with all its internal contradictions and slow-burning conflicts with occasional flare-ups. The current marches around the TIPNIS road-building issue display this dynamic perfectly. Indigenous groups and other opposition to the government plan are currently marching from the indigenous lands towards the capitol, protesting a proposed road that would run through indigenous lands and natural preserves. Now, this conflict is just the spectacular moment of visible flame that has erupted after years of friction between developmentalism and “pachamamismo”/indigenismo.

Obviously revolutionary fervor is fascinating with all its supercharged emotion… however, at stake is whether or not we deepen our understanding of the issues by examining history, and a continuing post-uprising reality that belies or at least tempers the promises of revolution. The Water Wars in Cochabamba, unfortunately, far from solved Cochabamba’s water problems (see this Wikipedia article for the more info on the conflict, and the current water problems). The Arab Spring was so exciting when Egypt’s people rose up. And now? How many outside the region know what’s going on? Have the Egyptian people founded a new society? Check out this radio story on Egypt now:

As I work on this film, constantly reflecting and deepening understanding of (r)evolutionary processes with so many other creative minds, working with words, images and sounds, I am constantly impressed by how slow and small real change is... and how misleading the spectacle can be. Working to preserve creative and critical memory of social history, pushing towards a more just future, is grueling. And unpopular. But it appears to me to be the only way to truly progress. Otherwise the spectacle of revolution overwhelms, burns and tramples the true, deep movements that permit baby steps (and occasional leaps) forward on solid ground.

I think filming is revolution, and postproduction/distribution nation-(re)building. Spectacular Movements, the documentary, is a project embedded in much larger projects, from Teatro Trono's plays and performances, to the struggle to bring justice to the perpetrators of historical atrocities, to understanding the roots of revolutionary crises, to delving into the formation of a creative-critical mestizo-urban-indigenous identity. These are not fast and furious, even if they are exciting. Guided by the humble model set by these deeper, slower movements, we continue the journey. Thanks for coming along.

The spectacular moments of 2000 and 2003, when Bolivia was a battleground, have given way to the past 7 years of working out how to construct a new model, with all its internal contradictions and slow-burning conflicts with occasional flare-ups. The current marches around the TIPNIS road-building issue display this dynamic perfectly. Indigenous groups and other opposition to the government plan are currently marching from the indigenous lands towards the capitol, protesting a proposed road that would run through indigenous lands and natural preserves. Now, this conflict is just the spectacular moment of visible flame that has erupted after years of friction between developmentalism and “pachamamismo”/indigenismo.

Obviously revolutionary fervor is fascinating with all its supercharged emotion… however, at stake is whether or not we deepen our understanding of the issues by examining history, and a continuing post-uprising reality that belies or at least tempers the promises of revolution. The Water Wars in Cochabamba, unfortunately, far from solved Cochabamba’s water problems (see this Wikipedia article for the more info on the conflict, and the current water problems). The Arab Spring was so exciting when Egypt’s people rose up. And now? How many outside the region know what’s going on? Have the Egyptian people founded a new society? Check out this radio story on Egypt now:

As I work on this film, constantly reflecting and deepening understanding of (r)evolutionary processes with so many other creative minds, working with words, images and sounds, I am constantly impressed by how slow and small real change is... and how misleading the spectacle can be. Working to preserve creative and critical memory of social history, pushing towards a more just future, is grueling. And unpopular. But it appears to me to be the only way to truly progress. Otherwise the spectacle of revolution overwhelms, burns and tramples the true, deep movements that permit baby steps (and occasional leaps) forward on solid ground.

I think filming is revolution, and postproduction/distribution nation-(re)building. Spectacular Movements, the documentary, is a project embedded in much larger projects, from Teatro Trono's plays and performances, to the struggle to bring justice to the perpetrators of historical atrocities, to understanding the roots of revolutionary crises, to delving into the formation of a creative-critical mestizo-urban-indigenous identity. These are not fast and furious, even if they are exciting. Guided by the humble model set by these deeper, slower movements, we continue the journey. Thanks for coming along.

Friday, September 2, 2011

Yesterday Bolivia's Supreme Court reached a verdict on the Black October case. The ex-military leaders that formed part of Gonzalo "Goni" Sanchez de Lozada's government were convicted for their role in the massacre in October 2003. This is a major landmark in the social and judicial process of dealing with the revolts and massacres of 2003. The young actors in our documentary bring the events that this trial dealt with to life, and through their play, their public discourse, and their street performance-protests they have formed part of the pressure on the government for there to be justice in this case. It has taken almost 8 years for us to reach this point.

This achievement is partial, and is part of a much larger movement. In terms of 2003, much remains to be done: most notably, the extradition of Goni and his ministers from the US and Peru. And above all, in Bolivia, Latin America and the world, other historic crimes must be brought to justice. For example, and most pressing throughout Latin America, the crimes of the dictatorships of the 60s-80s must be exposed and brought to trial. Only through ending impunity and reviving/applying collective memory can we avoid such atrocities in the future.

See our Spanish Blog for more information and articles.

The conviction of seven high-ranking former officials in Bolivia for

their role in dozens of deaths during anti-government protests in 2003

is an important step for justice, Amnesty International said today.

The conviction of seven high-ranking former officials in Bolivia for

their role in dozens of deaths during anti-government protests in 2003

is an important step for justice, Amnesty International said today.

Bolivia’s Supreme Court in Sucre yesterday sentenced five former senior military officers and two former ministers for their part in the events known as “Black October,” which left 67 people dead and more than 400 injured during protests in El Alto, near La Paz, in late 2003.

The clashes included soldiers opening fire on unarmed crowds during demonstrations sparked by opposition to a proposed pipeline to export natural gas through neighbouring Chile.

”These convictions are an important victory for the families of those killed and injured who have waited nearly eight years to see justice delivered after the tragic events known as ‘Black October’,” said Guadalupe Marengo, Deputy Americas Programme Director at Amnesty International.

The five military officers have received prison sentences ranging from 10 to 15 years, while the two former ministers were sentenced to three years.

Former President Gonzálo Sánchez de Lozada and former ministers Carlos Sánchez Berzaín and Jorge Berindoague fled to the USA soon after the “Black October” violence and are facing extradition. Several other former ministers and military officers fled the country when the charges were made public in November 2008.

Serious obstacles hindered the case, including the failure of the military to hand over relevant information and a lack of sufficient resources to allow many witnesses and victims to attend court in Sucre, a long way from El Alto.

“We hope that this ruling sets a positive precedent for the pursuit of lasting and impartial justice in other human rights cases in Bolivia,” said Guadalupe Marengo.

---

http://www.canadaviews.ca/2011/08/31/bolivia-former-officials-convicted-over-massacre/

------------------------

"I commend the Bolivian Supreme Court for its decision, which is an important step in the fight against impunity," Navi Pillay, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights said in statement.

"I also urge the government to take all necessary steps to ensure victims and their relatives receive suitable reparations and redress," she said.

On Tuesday two former ministers and five ex-military officers were each given prison terms of between three and 15 years for their role in a brutal crackdown that left some 65 people dead and injured 500 during a 2003 protest.

Retired General Roberto Claros Flores, former head of the Bolivian armed forces and Juan Veliz, former commander of the army, received the harshest punishment, with each sentenced to 15 years in prison.

Two other generals received prison sentences of 10 and 11 years, while a former navy admiral was sentenced to 11 years in prison.

And Bolivia's former Labor minister, Adalberto Kuajara, as well as its sustainable development minister, Erick Reyes Villa received sentences of three years each from Bolivia's high court.

The sentences ended years of legal wrangling following the brutal government crackdown during the regime of liberal president Gonzalo Sanchez de Lozada, now in exile in the United States.

The protests were against president Sanchez de Lozada's plan to sell natural gas to foreign countries through Chile, with which Bolivia has a century-old border dispute.

"I welcome this signal by yet another Latin American country that impunity for past human rights violations will no longer be tolerated," Pillay added.

--

http://www.expatica.com/ch/news/swiss-news/un-rights-chief-commends-bolivia-sentence-for-2003-massacre_172993.html

------------------------

This achievement is partial, and is part of a much larger movement. In terms of 2003, much remains to be done: most notably, the extradition of Goni and his ministers from the US and Peru. And above all, in Bolivia, Latin America and the world, other historic crimes must be brought to justice. For example, and most pressing throughout Latin America, the crimes of the dictatorships of the 60s-80s must be exposed and brought to trial. Only through ending impunity and reviving/applying collective memory can we avoid such atrocities in the future.

See our Spanish Blog for more information and articles.

Bolivia: Former officials convicted over massacre

by: Amnesty International

Bolivia’s Supreme Court has convicted seven former officials for

their role in the “Black October” massacre during protests in 2003.

31 August 2011

31 August 2011

Bolivia’s Supreme Court in Sucre yesterday sentenced five former senior military officers and two former ministers for their part in the events known as “Black October,” which left 67 people dead and more than 400 injured during protests in El Alto, near La Paz, in late 2003.

The clashes included soldiers opening fire on unarmed crowds during demonstrations sparked by opposition to a proposed pipeline to export natural gas through neighbouring Chile.

”These convictions are an important victory for the families of those killed and injured who have waited nearly eight years to see justice delivered after the tragic events known as ‘Black October’,” said Guadalupe Marengo, Deputy Americas Programme Director at Amnesty International.

The five military officers have received prison sentences ranging from 10 to 15 years, while the two former ministers were sentenced to three years.

Former President Gonzálo Sánchez de Lozada and former ministers Carlos Sánchez Berzaín and Jorge Berindoague fled to the USA soon after the “Black October” violence and are facing extradition. Several other former ministers and military officers fled the country when the charges were made public in November 2008.

Serious obstacles hindered the case, including the failure of the military to hand over relevant information and a lack of sufficient resources to allow many witnesses and victims to attend court in Sucre, a long way from El Alto.

“We hope that this ruling sets a positive precedent for the pursuit of lasting and impartial justice in other human rights cases in Bolivia,” said Guadalupe Marengo.

---

http://www.canadaviews.ca/2011/08/31/bolivia-former-officials-convicted-over-massacre/

------------------------

UN rights chief commends Bolivia sentence for 2003 massacre

02/09/2011 © 2011 AFP

The UN's rights chief on Friday welcomed a decision by Bolivia's top court to sentence two former ministers and five senior military officers to prison for their role in a deadly 2003 crackdown.

"I commend the Bolivian Supreme Court for its decision, which is an important step in the fight against impunity," Navi Pillay, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights said in statement.

"I also urge the government to take all necessary steps to ensure victims and their relatives receive suitable reparations and redress," she said.

On Tuesday two former ministers and five ex-military officers were each given prison terms of between three and 15 years for their role in a brutal crackdown that left some 65 people dead and injured 500 during a 2003 protest.

Retired General Roberto Claros Flores, former head of the Bolivian armed forces and Juan Veliz, former commander of the army, received the harshest punishment, with each sentenced to 15 years in prison.

Two other generals received prison sentences of 10 and 11 years, while a former navy admiral was sentenced to 11 years in prison.

And Bolivia's former Labor minister, Adalberto Kuajara, as well as its sustainable development minister, Erick Reyes Villa received sentences of three years each from Bolivia's high court.

The sentences ended years of legal wrangling following the brutal government crackdown during the regime of liberal president Gonzalo Sanchez de Lozada, now in exile in the United States.

The protests were against president Sanchez de Lozada's plan to sell natural gas to foreign countries through Chile, with which Bolivia has a century-old border dispute.

"I welcome this signal by yet another Latin American country that impunity for past human rights violations will no longer be tolerated," Pillay added.

--

http://www.expatica.com/ch/news/swiss-news/un-rights-chief-commends-bolivia-sentence-for-2003-massacre_172993.html

------------------------

Sunday, August 14, 2011

A Visual Timeline of the film

The young actors of Teatro Trono watch historical footage of the Gas Wars in 2003.

El Alto leads the protests over the exporting of national gas. The president flees after 84 die in clashes with the police and military.

Tintín and the other youth remember these events, and how it formed them,

just as they came of age as revolutionary artists.

The troupe debates how these events live on, how the current indigenous president, Evo Morales, both represents them more than ever, and had better watch out for their needs, or else...

Another actor, Maya reflects on the role of their theater in a larger project of liberation

The youth rehearse, and put the events of 2003 into a larger context of historical oppression.

They prepare for an upcoming tour in their Theater-Truck.

The play takes form through their collective creative process..

They explore their identity as urban youth born of indigenous rural migrants.

Traditional/Western clothes are the symbols they play with...

in Andean identity, cloth is everything.

in Andean identity, cloth is everything.

The tour quickly approaches, and the youth feel enormous pressure to get it ready in time, and begin to realize the enormity of what they're trying to represent.

Maya goes home between rehearsals, and helps her mother to cook.

Maya tells her mother about the play they are rehearsing, and how it's about the creation of El Alto. Her mother tells her why she migrated to El Alto from the countryside.

Tintín tells his father about their play, and how he will be playing a medicineman. His father is skeptical about his ability, and quizzes him about his Aymara language skills, and the names of the holy mountains he needs to invoke.

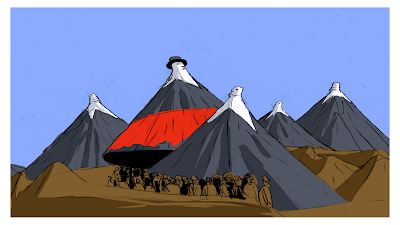

Animation: the sacred mountains are personified, the apus. One, a cholita, lifts her skirts, and from beneath emerge miners, who walk to the edge of the Altiplano above La Paz. There, they noisily build a city, El Alto, and out of the rubble from the construction a tall, colorful, recycled building emerges... Teatro Trono

Teatro Trono

At the top of Teatro Trono's building, Iván, the director of the organization,

writes dialogue for the youth's play

Iván thinks on the building's roof, overlooking El Alto and the mountains.

Iván describes the deeper social causes of the 2003 rebellion, the discontent at inequality that eventually exploded.

The troupe continues rehearsing, but also can't stop messing around,

their youthful energy distracting them constantly.

Iván scolds them, trying to get them back on track.

They do their best to incarnate those who died in the revolt...

... and using cardboard they project their images of the icons of the popular classes that revolted.

They develop their characters, these iconic figures, such as the Cholita, using projections of themselves with whom they improvise interactions.

Figure... projection... shadow... their identities multiply.

The troupe is invited to do a public performance in La Paz, representing

the coup d'etat that caused the last dictatorship. They travel down from frigid El Alto.

They perform without warning during a commemorative ceremony,

acting as thugs and the union leaders that were assassinated in 1980.

Their demand is to declassify the secret military files

that hide the identities of the perpetrators of crimes against humanity...

This protest is taken to the national military headquarters. The files about the Gas Wars are also classified... their declassification would begin the process of justice for the 84 who were shot dead.

The youth continue the protest with a spectacular march through La Paz.

Saturday, July 23, 2011

The youth go to their neighborhood market in Satellite City

In the market they buy an offering to bless the imminent tour in the Theater-Truck

The offering to Pachamama, Mother Earth

"Pijchando", chewing, coca

In front of the fire, the youth dare to speak of their greatest hopes for the future

Tintín improvises a dialogue with his character, el Yatiri, who speaks to him in Aymara. Tintín only partly understands, and this fact provokes a crisis where he decides he doesn't dare to manifest this dead medicineman. He decides to leave the role to the understudy, and not accompany the group on tour...

An animation shows the troupe leaving El Alto in the Theater Truck and going to the bus terminal. Everyone makes loads of noise in the truck... except Tintín.

At the terminal, the troupe gets on the bus for Cochabamba, and leaves Tintín behind.

The troupe and the German volunteers set up the Theater Truck for the first time

Ready for their first audience

They bring out the neighbors, their audience, with drums

Just before getting on stage, the actors realize that they are missing key props, and it's obvious that they aren't as ready as they had thought. The lack of leadership is obvious.

They put on the play anyways

And they get the attention and laughter of their audience

Despite this, as they discuss the next day, it's obvious the troupe is not happy with the show. There were many errors, and Maya in particular doubts that they have affected the audience as much as they had hoped.

The youth continue their tour, but there's little connection with their audience,

on and off stage

on and off stage

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)